UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland is the first hospital in the West to offer the newly approved gene therapy to treat beta thalassemia, a rare, genetic blood disorder that causes severe anemia, the need for life-saving blood transfusions and the risk of fatal organ failure.

The Oakland hospital was one of three sites in the United States to host trials of Bluebird Bio therapy, approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in August 2022. treatment Zynteglo and is among the first to treat the patient.

A 9-year-old patient from Oakland received a single infusion treatment on August 15, 2023. If successful, the treatment could eliminate the need for more blood transfusions, allowing the child to produce healthy blood cells and live a normal life.

“This new treatment could change the lives of beta thalassemia patients, who have required complex and expensive blood transfusions, month-to-month,” said Mark Walters, MD, director of the pediatric Bone Marrow Transplant program at UCSF Benioff Oakland and chief of pediatrics. Hematology at UCSF, who led the Oakland clinical trial.

Walters, a professor of hematology at UC San Francisco, said: “The reason gene therapy is so exciting is because it’s so individualized. “We don’t have to look for a brother or sister or someone else to donate – we can use the patient’s own blood cells.”

Healthy hemoglobin in 90% of patients

Beta thalassemia is considered one of the most common rare diseases in the US, affecting approximately 1,500 people nationwide. Because this strain provides natural resistance to malaria, it is common in areas of the world where malaria is common and is most common in the Mediterranean, Middle East and South Asia.

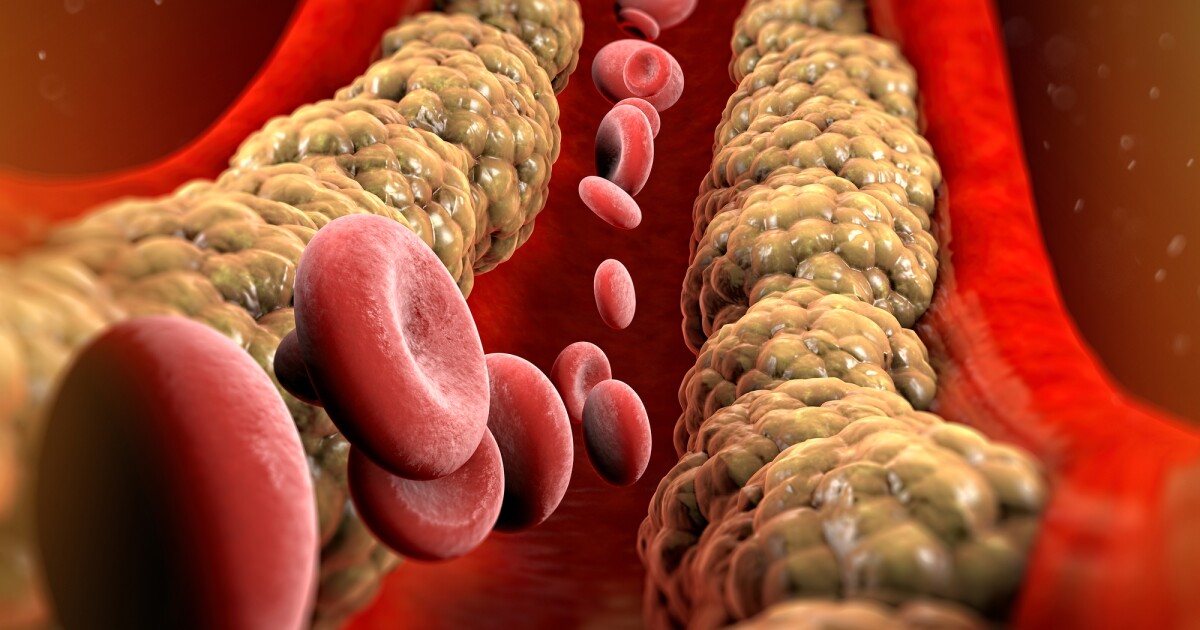

It is usually detected by newborn screening, and treatment begins at 6 months of age to overcome having too few red blood cells to sustain life. Patients also need regular treatment to reduce high levels of iron caused by blood transfusions, which can affect the function of their heart, liver and endocrine organs such as the pancreas and pituitary gland, which are needed for growth and development.

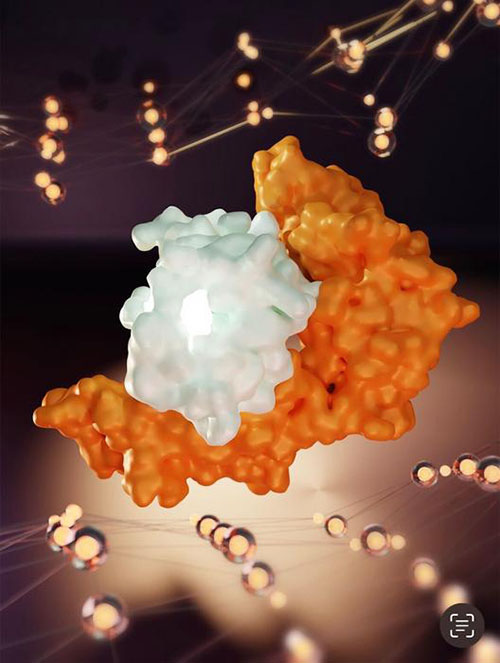

Treatment involves removing some of the patient’s blood cells and genetically engineering them to replace a defective gene that produces little or no hemoglobin – the protein used by red blood cells to carry oxygen to tissues throughout the body.

After the transplanted cells are prepared in the lab, the patient receives a strong dose of chemotherapy to kill the existing blood cells with thalassemia defects and replace them with newly regenerated blood. The new cells are then injected into the patient’s blood, where they travel to the bone marrow and produce healthy blood.

The process involves several months of close medical monitoring to track the patient’s blood count and detect possible infections after chemotherapy.

In a clinical trial, which ended in March 2022, Walters and his colleagues found that this treatment produced healthy hemoglobin in 90% of patients. Since the trial ended, those patients have been able to stop other ongoing treatments for their condition.

“The reason gene therapy is so exciting is that each person is their own donor.”

Mark Walters, MD

#Oakland #Hospital #West #Pioneer #Beta #Thalassemia #Drug