This century, Australia has been hit by more and more frequent fires. The 2019-20 Black Summer fires were the worst on record for area burned and property loss.

How much climate change has contributed to this increase is a hot topic. Forest fire risk depends on four variables: fuel amount and condition, fire weather and ignition sources. Disentangling these various influences is difficult, so the role played by warming climate is highly debated.

Fire-climate measures fire risk on a daily basis, while fire-climate regime measures fire risk over a seasonal and long-term period. Our research shows almost everywhere in Australia is now in a different fire climate than it was 20 years ago, with falling relative humidity a key factor. Previous research has identified this sudden jump in fire risk.

What caused the fire climate to change? Conventional scientific wisdom assumes that the climate response to increased emissions is slow and synchronous. When rapid changes occur, it is often thought to be due to climate change. But that didn’t happen here.

Rod Blakers/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-ND

Much of Australia’s fire climate regime has changed

Fire weather is calculated using the Forest Fire Danger Index, which takes into account vegetation dryness, windspeed, temperature and relative humidity.

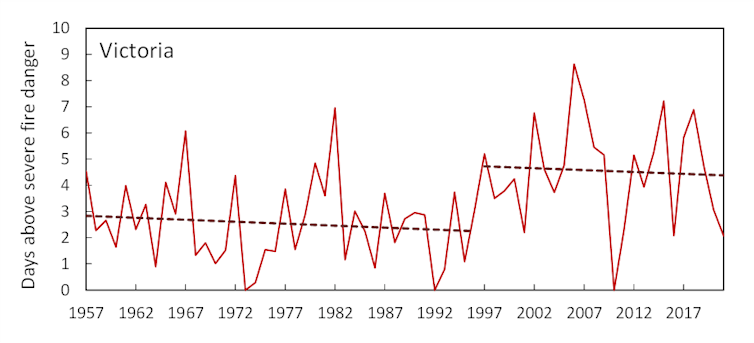

Obtaining reliable long-term records using these measures is difficult, so we used high-quality annual and annual climate effects to estimate annual fire weather in various regions of Australia from 1957-58 to 2021-22.

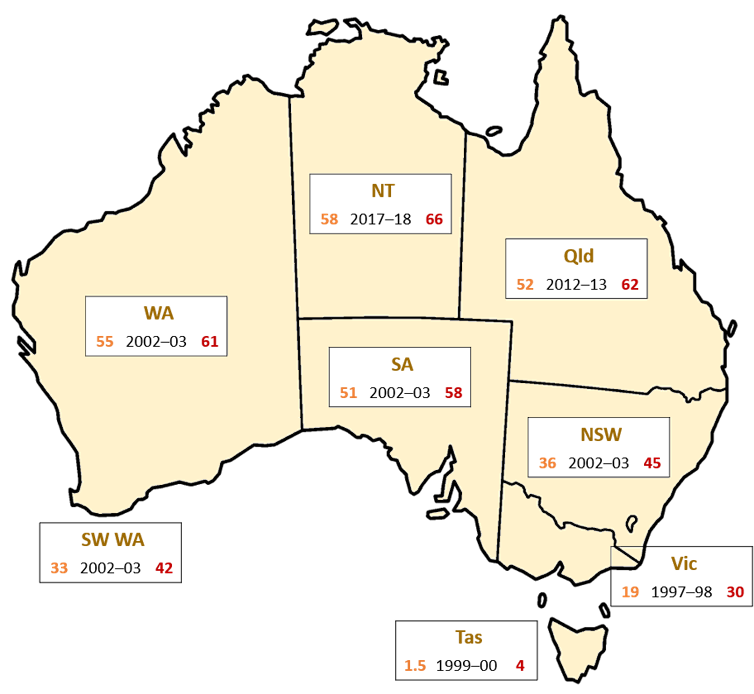

We tracked changes in the fire hazard index over a 64-year period for all states and the Northern Territory. We also looked at different sub-regions such as south-west Australia. What we found was surprising. Rather than being promoted in sequence, the fire commanders are followed in a single line – and then jump off suddenly. In many regions and regions, that happened around the year 2000.

There is no evidence of a long-term trend. Instead, the data show a transition from one stable fire climate regime to another.

We are already seeing this change play out. Whenever you see a news article about wildfires burning in places that aren’t used to burning, it’s probably because of the changing fire climate. Consider the fires that ravaged Tasmania’s highlands in 2016, killing many old-growth pines and King Billy pines.

When did these jumps occur?

Here is where each region transitions from fire control to the next:

You can see changes in the number of days above “high fire danger”.

Given to the authorCC BY-ND

When we presented this research to Greg Mullins, former Fire and Rescue Commissioner in New South Wales, he said

it is completely consistent with what firefighters face around the world: frequent, intense, and sometimes devastating bushfires that are difficult to control.

Is it really that bad? Oh yeah.

For example, what would have been one in ten bad fire seasons under the previous regime (which occurred once every ten years) became, on average, one fire season in two under the second regime.

That means that at least 10% of fire years occur every second year.

When we looked at the worst fire years – the worst year in the 20th fire season – the change was surprising. On average, we now see this age twice every five years.

Why did fire weather conditions suddenly change?

That’s a big question.

To find out, we analyzed all the available input variables for changing the regimen and evaluated their impact on the results. We found the wind speed is nothing. The change in rainfall had little effect.

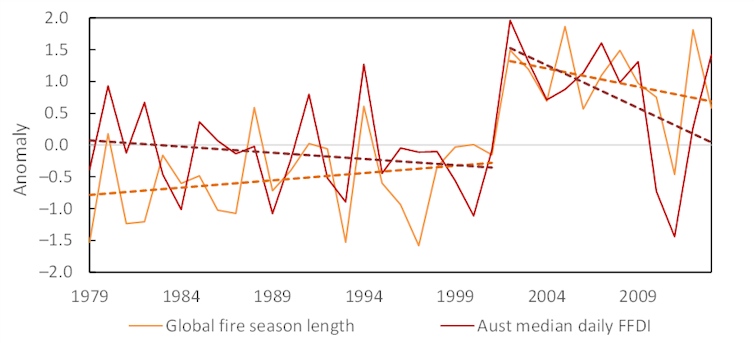

So what was it? We found the main driver was relative humidity combined with high daily temperatures during the fire season. Recently, we examined global humidity data and found a large downward trend in humidity. In South Equator, that happened in 2002. In the Northern Hemisphere, it happened in 1999.

The reduction in humidity in every region of Australia has been closely followed by a shift to higher fire season temperatures, fueled by drier soils.

We also examined average fire duration from 1979 to 2013 for management changes, finding a sharp increase in 2002. It’s also another year Australia’s fire danger has jumped.

Data from Lucas and Harris 2019 and Jolley et al. 2015

The consequences of this change are profound. Unprecedented fires in Canada and Europe, devastating fires in Hawaii and the constant increase in wildfires around the world have their roots in low humidity, which leads to high daytime temperatures. That, in turn, creates these new dangerous fire systems.

Why haven’t we heard of these sudden changes in fire weather? Another reason is that most of our models are built on the assumption that the accumulation of heat trapped by greenhouse gases leads to linear changes elsewhere.

But as this year’s climate chaos suggests, this assumption may be unfounded.

In our previous research, we found zero of 32 climate models were able to reproduce sudden changes in relative humidity across the globe.

Read more: ‘Australia is sleeping’: bushfire scientist explains what Hawaii disaster means for our combustible continent

What does this mean for this fire season of the year?

Much of New South Wales, Queensland, the Northern Territory and north-west Victoria are already dry, although large forests will retain moisture after years of rain. Grass fires are already raging in the Northern Territory.

That means the biggest risks to this species will be in grasslands, woodlands and urban pastures. Widespread forest fires are probably less likely. But large fires will return if dry conditions continue.

In fact, in today’s climate, the land is drying out much faster than before, leading to droughts that change from very wet to very dry in a short period of time.

Remember – this current fire system is not permanent. As the weather gets hotter, it’s entirely possible that our fire regimes could turn to something more dangerous. Ensuring that our climate models can predict these changes is an urgent task.

Read more: Australia’s dark summer of fire was unusual – and we can prove it

#Fire #regimes #Australia #changed #suddenly #years #falling #humidity